Voices from Zoroastrian Iran

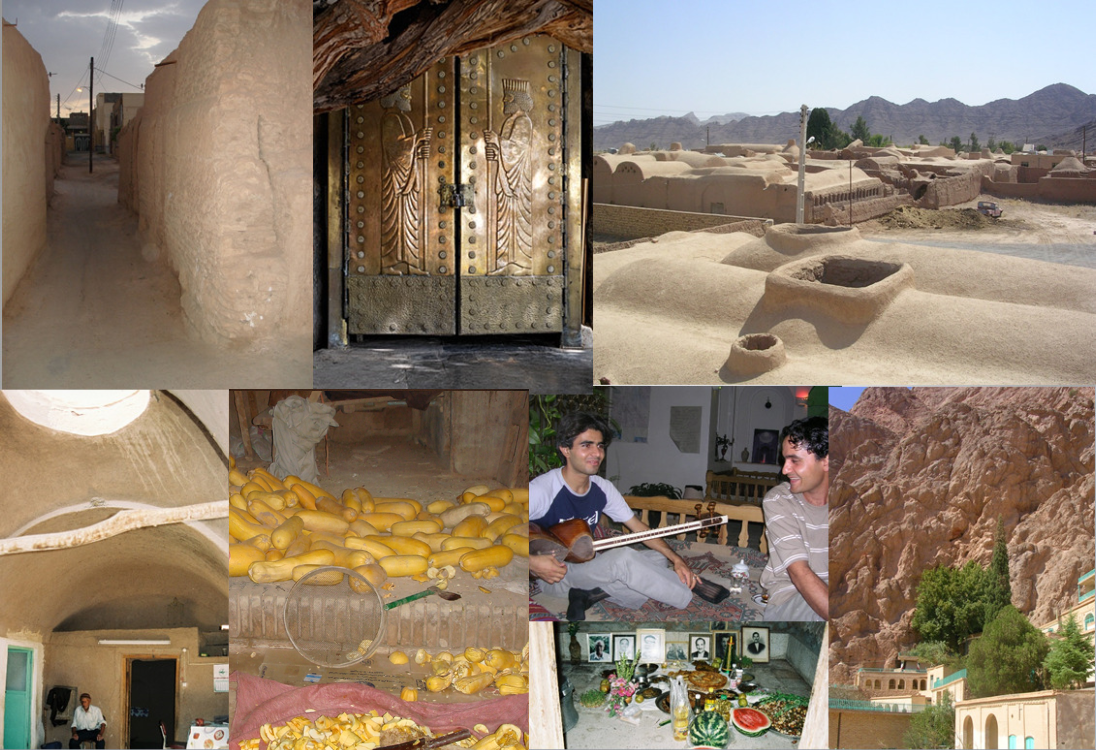

Landing page image for the collection ’Voices from Zoroastrian Iran’. Click on image to access collection.

| Language | Zoroastrian Dari |

| Depositor | Sarah Stewart |

| Affiliation | SOAS University of London |

| Location | Iran |

| Collection ID | 0460 |

| Grant ID | LRG-42461 |

| Funding Body | British Academy |

| Collection Status | Collection online |

| Landing Page Handle | http://hdl.handle.net/2196/7452521f-31bc-4f80-9870-27cf9fab2d06 |

Showreel

Summary of the collection

An oral studies project that maps the remaining Zoroastrian communities in Iran. In this deposit of 330 interviews Zoroastrians speak about their lives before and after the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Topics include religious and devotional life as well as issues such as emigration, education and marrying outside the community.

Zoroastrians were interviewed in urban centres wherever they live in Iran today (Kermān, Ahvāz, Shirāz, Esfahān, Tehrān and Yazd) and in the villages surrounding the city of Yazd where Zoroastrians still live or own property and/or land.

Participants in this study refer to community leaders, historical figures, local events, teachers and religious texts that have shaped their views and understanding of the religion. They also speak about the events and circumstances in recent history (for example the Iran-Iraq war) that have had an impact on their lives.

Interviews were conducted mainly in the Zoroastrian Dari language, which is under threat as villagers move to urban centres and often emigrate abroad thereafter. Dari is a spoken rather than a written language so young people, who may speak Dari at home, use Persian to type and communicate electronically via social media networks thus further distancing themselves from the language of their parents and grandparents.

Group represented

The Zoroastrians of Iran number less than 25,000 today. The majority live in Tehrān and the remainder in the cities of Yazd and Kermān. There are small Zoroastrian communities consisting of 100-300 individuals who live in the cities of Shirāz, Esfahān and Ahvāz. Each has its own fire temple and community centre as well as an anjoman or local council. Some few hundred Zoroastrians still live in the Zoroastrian villages of the Yazdi plain.

The history of Zoroastrianism and the legends attached to various locations are ever-present in the minds of those interviewed for this project.

Zoroastrianism originated in the distant past developing from a religion that once belonged to the ancestors of tribes that settled in Iran and Northern India. It is believed to have become established in Central Asia sometime in the second millennium BCE and from there to have spread across the Iranian plateau to western Iran. It became the foremost religion of three Persian empires: Achaemenid (c. 550-330 BCE), Parthian (c. 274 BCE – 224 CE) and Sasanian (224-651 CE).

Central to Zoroastrianism is the profound dichotomy between good and evil, the idea that the world was created by God, Ahura Mazdā, in order that the two forces could engage with one another, the belief in an afterlife that is determined by the choices individuals make while on earth, the final defeat of evil for all time and a return of the world to its once perfect state.

At the time of the Arab conquest of Iran in 651 CE Zoroastrianism was the religion of a powerful nation-state with a highly developed administrative and legal system. Thereafter, it became that of a minority religion under duress. The conjoining of theology and jurisprudence that informed the new state ideology meant that non-Muslims could never enjoy full citizen’s rights unless they converted to Islam. However, as non-Muslims belonging to a monotheistic faith, along with Christians, Sabeans and Jews, they were granted a special status: ahl al-Ketāb, or ‘people of the book’. This category gave them the status of dhimmi, or ‘protected persons’ and certain rights under Islamic sovereignty and within the legal system. Payment of the jezyeh, or poll tax by all dhimmis was a factor that contributed to their economic hardship and they were bounded by various restrictions in everyday life. These included the architecture of their houses, the clothes they were permitted to wear, modes of travel and general comforts such as the use of wind-towers.

According to Parsi (Zoroastrian) tradition, a band of Zoroastrians set sail from Iran to escape the persecution of the Muslim majority in Iran. They landed on the coast of Gujarat (India) where they were allowed to stay and practice their religion. The date of their arrival is contested but it is generally agreed that Zoroastrians from Iran began to establish themselves in Gujarat sometime between the 8th and the 10th centuries. By the beginning of the Qajar period in Iran (1779-1924) the Zoroastrian population numbered less than 10,000.

The fortunes of Zoroastrians in Iran began to change in the mid-nineteenth century with reforms that were the result of efforts by the Parsi emissary, Maneckji Limji Hataria, to Iran in 1854. Parsi philanthropic donations to the Iranian Zoroastrian community led to the establishment of schools, hospitals and community centres. Fire temples and dakhmehs were repaired and institutions such as the anjomans, both priestly and lay, gave a formal structure to community affairs governance. The Constitutional Revolution of 1905 led to the first Iranian parliament and the election of an Iranian Zoroastrian representative.

The sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, the Avestā, were composed and transmitted orally in an ancient Iranian language, Avestan. At the heart of the Avestā are the Gāthās, believed to have been composed by Zarathustra (Gr. Zoroaster), after whom the religion is named. From around the 4th century BCE, Zoroastrian priests began to translate Avestan texts into the Middle Persian idioms that had replaced the Old Iranian dialects. Avestan texts have survived today as the result of a long period of oral transmission in which they were preserved by priests reciting them in religious ceremonies and by the laity in their daily prayers. They were probably not written down until late in the Sasanian period (224–651 CE), in an alphabet designed especially for the purpose.

During the ninth century there was a proliferation of Zoroastrian religious texts in Middle Persian and also exchanges of ideas between Zoroastrian scholar-priests and their conquerors, as well as with the new converts to Islam. Middle Persian gave way to the New Persian language, which began with the poetry that emerged in the eastern provinces and known at the time as dari. As a successor to the Old Persian and Middle Persian of Fars it differed from the modern, spoken Dari, of Zoroastrians today, which belongs to the dialectical group of Iranian languages of north-eastern Iran.

Language information

The Zoroastrian Dari language is associated traditionally with the Zoroastrian communities of Yazd and Kermān and the outlying villages of both cities.

Today Dari and its various sub-dialects are spoken by Zoroastrians in Yazd and villages of the Yazdi plain, where a few Zoroastrians still live or maintain and visit their ancestral homes. Some villages became suburbs of the city and inhabitants still speak their village dialect. Family names of interviewees show that although families migrated to the cities they did not usually move from village to village – a reason why the discrete Dari dialects survived for so long. Some village dialects continue to be spoken across generations by families who have resettled in cities such as Tehrān, Shirāz and Esfahān. Traditionally, Zoroastrian Dari was maintained down the centuries as a language that was not readily understood by non-Zoroastrians.

By 1962, all Zoroastrian families from the villages outside Kermān had moved to the city and there are now very few who speak Kermāni Dari.

Estimated Zoroastrian Population (2017)

Special characteristics

The deposit provides a mapping of the remaining Zoroastrian communities in Iran. This has not been done before and is unlikely to be undertaken again as people disperse from the areas where the Dari language is spoken.

Collection contents

The historical context of Iranian Zoroastrianism is ever-present in interviews for this project. Zoroastrians are well-informed about their ancient history – one that has become part of Iranian historical consciousness and which gives Iranians a sense of who they are today. Zoroastrians talk about the historical links with their co-religionists in India and contacts are maintained between the two communities.

Many of the key elements of minority status have been in existence for over a thousand years, for example, the prohibition of proselytizing and worship in public, and marriage between a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man; likewise, the laws of inheritance and the penal code that discriminate against religious minorities. Participants speak about the interaction with other minority groups and also the discriminatory customs that governed everyday life, space and travel for Zoroastrians. For example, the purity laws that prohibited religious minorities from drinking in public water fountains, are within living memory for the older generation today. Zoroastrian internal governance via the anjomans is another important topic since the wealth of the community is embedded in endowments of one sort or another (owqāf). It is these that enable the religious ceremonies and annual festivals, gāhāmbārs, to be maintained. The Zoroastrian representative in the Majles is recognized as being an important factor in the life of the community as a whole insofar as this is the means by which positive change to minority status can be effected.

Emigration is a topic that looms large as young people leave Iran to seek educational and job opportunities abroad; opinion is divided as to whether or not this is to be encouraged since it divides families – usually leaving older members behind. Another area of divided opinion concerns the importance of maintaining religious rituals and the efficacy of praying in a language (Avestan) that is no longer understood. Only the Gāthās are considered immutable – although while some seek to understand the meaning of the words, others adopt the more traditional view that they are beyond literal understanding. Religious ideas are often summarized in the central tenet ‘Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds’ but discussions also take place that reflect the difference between reformist and more traditional approaches to doctrine and teaching.

Zoroastrians embraced Persian literature and poetry probably from the time of its early composition. The stories and legends they learn by heart from childhood are from the Shāhnāmeh, many of which derive ultimately from Avestan texts such as the Yashts. Villagers speak of gatherings where poetry is recited and sometimes even composed and of these gatherings as belonging to a long-lived tradition. In interview priests often draw on Persian poets to illustrate a religious teaching or a point of view.

The bundles in this deposit are all audio files. They number 330 interviews, some of which are in multiple files and several hours in length.

Collection history

Scholarly work on Zoroastrianism has traditionally focused on the religious texts in the Avestan and Pahlavi languages. The language of Zoroastrian Dari has rarely been the subject of study. This deposit provides a rich linguistic source for future research. The mapping of the Zoroastrian communities Iran-wide means that the sub-dialects of the Dari language are represented here. In addition, future generations of Zoroastrians in the diaspora will be able to listen to the language spoken by their forebears in Iran.

The research for this project followed the award of a British Academy major grant in 2007. It was was undertaken by the primary investigator, Sarah Stewart, in collaboration with the London-based researcher and former SOAS student, Mandana Moavenat, together with a small team in Iran.

The methodology for collection of data was developed in collaboration with Professor Philip Kreyenbroek, and Mrs Shehnaz Neville Munshi for a project on the Parsis in India. In both projects, the key person chosen to undertake the majority of interviews was a prominent member of the Zoroastrian community who had undertaken training by the primary investigator on the use of equipment and interview techniques. A qualitative approach was adopted whereby interviews took place in a relaxed atmosphere – usually in a person’s home.

The interviews are divided into two categories, (A) and (B). The interviews in group (A) are essentially ‘fact-finding’ interviews related to aspects of community life. Interviewees in this category were asked for biographical and demographic information, and about their religious lives and education.

The second category of interviews (B) was conducted with people who were prepared to give a fuller account of their religious lives, and to express their personal views. For the most part these should be treated as narrative accounts that illuminate and bring to life factual material, experiences and religious beliefs.

Related Publications

Sarah Stewart, 2018. Voices from Zoroastrian Iran: Oral Texts and Testimony. Vol. I: Urban Centres

Sarah Stewart, 2020. Voices from Zoroastrian Iran: Oral Texts and Testimony. Vol. II: Urban and Rural Centres: Yazd and Outlying Villages

Other information

This collection is accompanied by Part 1 of a two – part volume:

Stewart, Sarah (2018) Voices from Zoroastrian Iran: Oral Texts and Testimony (Part 1: Urban Contexts: Kerman, Tehran, Ahvaz, Esfahan, Shiraz) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Interviews from Yazd and the villages are currently being digitized for this collection. They will be accompanied by Part 2 of the volume:

Stewart, Sarah (2019) Voices from Zoroastrian Iran: Oral Texts and Testimony (Part 2: Urban and Rural Contexts: Yazd and Outlying Villages) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

The names of interviewees in recordings for this collection have been muted as far as possible. This means all recordings start approximately 30 seconds into the interview.

Acknowledgement and citation

To refer to any data from the collection, please cite as follows:

Stewart, Sarah. 2018. Voices from Zoroastrian Iran: an archive of Zoroastrian religious, cultural and social material in Zoroastrian Dari and Persian. Endangered Languages Archive. Handle: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-0010-9FB6-9. Accessed on [insert date here].