Documentation and description of Maleku (Chibchan, Costa Rica)

From left to right: Carmen Elizondo Mojica, J. Aniceto Blanco Vela (†) & Lillian Elizondo Benavídez. Picture taken at Caño Negro (Toro Jami) by Roberto Herrera Miranda. February, 2020. Landing page image for the collection ‘Documentation and description of Maleku (Chibchan, Costa Rica)’. Click on image to access collection.

| Language | Maleku (ISO639-3:gut) |

| Depositor | Roberto Herrera Miranda |

| Affiliation | University of Leipzig, INALCO SeDyL (CNRS), University of Göttingen |

| Location | Costa Rica |

| Collection ID | 0405, 0576 |

| Grant ID | SG0372, IGS0345 |

| Funding Body | ELDP |

| Collection Status | Collection online |

| Landing Page Handle | http://hdl.handle.net/2196/ae2d105e-d5de-4c2c-a8cb-6402e3e70931 |

Summary of the collection

Group represented

Language information

English: Maleku, also known as Guatuso, is spoken in the northern plains of Costa Rica, in a territory much smaller than what has been allotted to them by the government since the second half of 20th century. It is presently spoken by approximately 300 speakers, none monolingual, in three small villages stretching along 6km of gravel road from the highway connecting the towns of Guatuso and La Fortuna, a tourist center that lures many of the younger community members to learn English and work in the industry. By comparison, the ancestral Maleku territory spanned the basin of the Frío river and its tributaries, stretching until the border with Nicaragua. Approximately 17 to 23 Maleku settlements were documented in this area during the 19th century. In the present, the language is mostly spoken in three communities in the indigenous reservation, with very minor variation among these speakers.

Maleku is one of the only extant members of the Votic branch of the Chibchan family, together with the almost extinct Rama of Nicaragua (Constenla Umaña 2012). The language family extends from western Honduras (where the also endangered Pech is spoken) to Northern South America with the highest linguistic density found at the Costa Rica-Panama border.

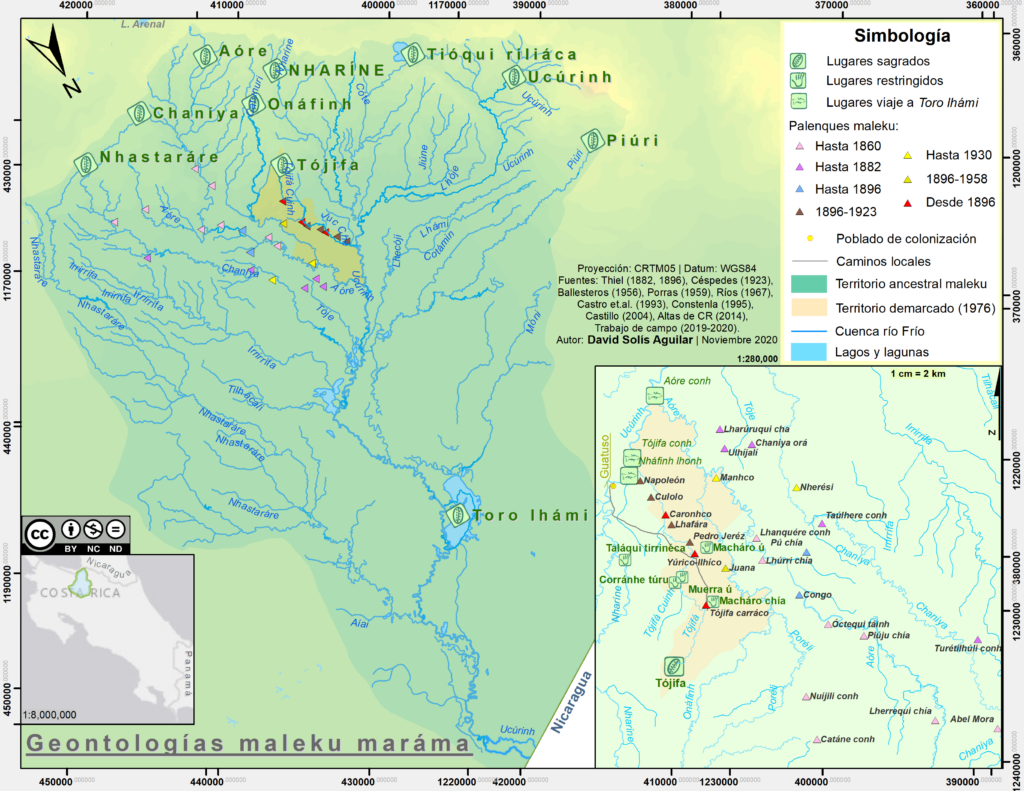

The map below shows the approximate ancestral Maleku territory, including culturally relevant sites, as well as the current settlements, according to Solís Aguilar, D. A. (2021).

Special characteristics

English: The documentary aspect of this project has focused on the bio-cultural relevance of natural areas, particularly Toro Lhami (or Toro Jami, the Caño Negro wildlife refuge), a wetland area traditionally visited by boat along the Ucurinh (Río Frío). The region along this and other rivers, which flow into the wetlands, are considered to constitute the Malekus’ ancestral territory. It hosts a series of fishing, hunting and resting sites, as well as others relevant to the Maleku ontology, for example, sacred and forbidden sites. Boat access to some of these places has been restricted in the last decades. Much of the IGS project is devoted to the documentation and description of these boat trips and the activities which used to take place before, during and after them, both from the travelers’ perspective as well as from their families’. Two trips to Caño Negro, by boat and car, with a small group of Maleku elders form part of this collection. During these trips, names of resting, fishing and hunting sites were recorded and photographed. The Malekus’ video-recorded accounts also highlight the relevance of other perhaps lesser-known sites located at nearby rivers, waterfalls and lakes, such as Nharine Chia and Cote Cha Iriliaca, etc. The contribution of the researcher of Human Geography David Solís Aguilar (Colegio de Michoacán, México), who joined several of our interviews during my field trip in 2020, has been crucial for this documentation task.

Another dominant theme in the personal narratives recorded are the Malekus’ trips to Tilarán, a small and difficult to access town close to the Arenal Volcano and the hunting trips to the Tenorio region. Several Maleku families used to travel there on foot across the forest to sell peach palm fruits (pejibayes, `juma’). Sometimes, they would venture as far as Cañas and Liberia in Guanacaste to sell their produce. These seasonal trips continued for several decades up until turn of the 21st century. The hunting trips to the area surrounding the Tenorio Volcano are still remembered by José Aniceto Blanco Vela (†), one of the eldest speakers. His account on these trips has also been documented. Finally, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic in the community, as well as the land recuperation movement that accompanied this last period of the IGS project have also been an important documentary aspect of this project. Online tools were employed for this task, as needed.

The photographs below show Alfredo Acosta Blanco fishing mojarra (jararanh, Cichlasoma sp.) at Caño Ciego (Irrirrifa Conh), and Carlos López Lacayo showing Muerra U in Tonjibe. The photos were taken by Roberto Herrera Miranda in February and January 2020 respectively.

Alfredo Acosta Blanco fishing mojarra (jararanh, Cichlasoma sp.) at Caño Ciego (Irrirrifa Conh). Photo taken by Roberto Herrera Miranda. February, 2020.

Carlos López Lacayo showing Muerra U in Tonjibe. Photo taken by Roberto Herrera Miranda. January, 2020.

Collection contents

English: As of late 2022, the Maleku collection contains over 100 hours of video and audio recordings available to registered users. These have been collected during the SG and the IGS projects thanks to the participation of 24 speakers, ages 25-70, from the three Palenques in Maleku territory.

The corpus contains (semi-)spontaneous recordings including traditional and personal narratives, interviews and demonstrations, etc., most of which have been translated (into Spanish) and transcribed in ELAN and are already available in the archive. A portion of these transcriptions has also been glossed. Additionally, sessions with stimulus materials and elicitation tasks have also been processed and deposited.

The main research outcome of the SG project was a Master’s thesis on Maleku’s valency affecting operations and valency classes (Herrera Miranda 2017). At the end of the IGS project, a dissertation on Maleku morphosyntax and information structure will be deposited. Further, the final collection contemplates the creation of a lexical database with items gathered from the legacy materials as well as from spontaneous recordings and elicitation sessions.

The production of materials for the communities’ schools was also planned as part of these projects. Language learning posters were produced and distributed in the local schools in 2017. All recorded sessions will be made available to community members at a repository in Palenque Margarita.

Collection history

English: The Maleku corpus has grown in size and representativeness since the small grant project started in 2015 (SG0372), thanks to the collaboration of over 20 speakers of different ages from the three main Maleku communities.

Most of the video recordings gathered so far have been translated into Spanish and transcribed with help of two native speakers. These include botanical sessions, demonstrations of traditional handicrafts and dishes, interviews, traditional and personal narratives, trips with multiple speakers, as well as sessions using stimulus materials.

Three short fieldwork phases were carried out between 2015 and late 2017. After the SG pilot project, I went back to the field in 2019, 2020 and 2022 for longer periods of time.

The photograph below shows Rosa Álvarez Álvarez explaining the uses of the cacao (`caju’). Also shown in the picture is a traditional sack made from burio (`porelenh’, Heliocarpus appendiculatus). The photo was taken by Roberto Herrera Miranda in January 2020.

Rosa Álvarez Álvarez explaining the uses of the cacao (caju). Also shown in the picture is a traditional sack made from burio (porelenh, Heliocarpus appendiculatus). Photo taken by Roberto Herrera Miranda. January, 2020.

Other information

English: The materials in this collection provide a major contribution to the depositor’s PhD research at the Georg August Universität Göttingen and Inalco (Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales), which will culminate in a dissertation on morphosyntax and information structure in Maleku.

The transcriptions deposited follow the orthographic conventions established by Constenla Umaña (1998). When transcribed by native speakers, only their Spanish orthography was sometimes altered. Original written resources can be requested from the principal investigator.

None of the materials in this collection may be used as evidence in a court of law.

References

English: Castillo Vásquez, Roberto. 2004. An Ethnogeography of the Maleku Indigenous Peoples in Northern Costa Rica. Ph.D. thesis, University of Kansas, Kansas City.

Castillo Vásquez, Roberto. 2005. El territorio histórico Maleku de Costa Rica. Revista Reflexiones 84.1, pp 71–86.

Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. 1998. Gramática de lengua Guatusa. Heredia, Costa Rica: EUNA, 1st ed.

Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. 2012. Chibchan languages. The Indigenous Languages of South America. A Comprehensive Guide. eds. Lyle Campbell and Verónica Grondona. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. 391–440.

Herrera Miranda, Roberto E. 2017. Valency classes in Maleku. Master’s thesis, Universität Leipzig.

INEC, Costa Rica. 2011. Costa Rica: Población total en territorios indígenas por autoidentificación a la etnia indígena y habla de alguna lengua indígena, según pueblo y territorio indígena. Tech. rep., Instituto nacional de estadística y censos. URL: https://www.inec.cr. Accessed: June 23, 2020.

Solis Aguilar, David. 2021. Socioespacialidades en el territorio originario Maleku de Costa Rica. Master’s thesis, El colegio de Michoacán, México.

Acknowledgement and citation

English: Users of any part of this collection should acknowledge Roberto Herrera Miranda as the principal investigator, data collector and researcher as well as the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme as funder of the project. The words and images of the individual Maleku speakers should be acknowledged by name. Any other contributor who has collected, transcribed or translated data or was involved in any other way during the SG and/or IGS project should be acknowledged by name. This information has been included in every bundle’s metadata.

To cite the entire collection, please use the following format:

Herrera Miranda, Roberto. 2015-2022. A documentation and description of Maleku (Chibchan, Costa Rica). Endangered Languages Archive. Handle: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-000F-BF4F-9. Accessed on [insert date here].

To cite the individual items within the collection, please use the following format: Last Name, Name (speaker), Roberto Herrera Miranda (researcher). [year collected]. Title of resource (format, unique ID). Endangered Languages Archive. Handle: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-000F-BF4F-9. Accessed on [insert date here].

I would like to thank Carlos López Lacayo (Poto), Alfredo Acosta Blanco, Rosa Álvarez Álvarez, José Aniceto Blanco Vela (†), and Lilian Elizondo Benavides for their invaluable support, as well as everyone who kindly opened their doors at one time or another and guided me throughout these years. Most transcriptions, translations, and organizational aspects of this project were possible thanks to the help of Poto and Alfredo. ¡Afepaquian ni marama naracarrayeca. Poi marama micua colonhafa ni malainheca macorroca malecuco!

Mención especial merece don José Aniceto Blanco Vela, quien nos dejó en junio del 2023. Aniceto fue un pilar en la comunidad malecu y uno de los hablantes más fluídos de la lengua. Así mismo, fue uno de los colaboradores principales de este proyecto. Expresamos nuestras sinceras condolencias a sus familiares.

Arraonhe chari ni José Aniceto Blanco Vela, oti nio carracofa mauchiye. Aniceto matoquitaiquica jonh chi Caronhco ofa eneque marama malecuco. Taca oti ninhafa chari lecu jaicaco iuraje, ninhafa jue nenhca chatifa rricuye, tia ni majueca lecu jaica.