Shangaji. A Maka or Swahili Language of Mozambique. Grammar, texts and wordlist

Landing page image for the collection ’Shangaji. A Maka or Swahili Language of Mozambique. Grammar, texts and wordlist’. Click on image to access collection.

| Language | Shangaji |

| Depositor | Maud Devos |

| Affiliation | Leiden University |

| Location | Mozambique |

| Collection ID | 0197 |

| Grant ID | IPF0075 |

| Funding Body | ELDP |

| Collection Status | Collection online |

| Landing Page Handle | http://hdl.handle.net/2196/e49bdff6-9d6d-42dd-a8fd-fb63ee1ac248 |

Summary of the collection

Shangaji is spoken in three small villages in the Nampula province of Mozambique. The collection focuses on the variant spoken in Naatthembo village, just west of the Sangage peninsula which begins north of Angoche town. Naatthembo has more or less 4000 inhabitants and represents the major Shangaji speaking centre with the two other locations; Nakonya village and the Likookha area in Mogincual adding more or less 500 and 700 speakers to this number of speakers which is in decline due to a lack of intergenerational language transfer. Nthamala village, some 10 km away from Naatthembo, no longer has Shangaji speakers because of a complete shift to the regional lingua franca Makhuwa (Enlai). The Shangaji collection thus responds to an urgent documentation need, also because the language is one of four coastal languages that are believed to bear traces of the Swahili world which once stretched from Somalia to the south of Mozambique.

Group represented

The materials within this deposit focus on the Shangaji variant spoken in Naatthembo village, some 40 km north of Angoche in the Nampula province of Mozambique. Naatthembo village has more or less 4000 inhabitants. Although close to the Indian Ocean, it is an isolated village which is best reached by driving north on the Sangage peninsula and then crossing the tidal Nlonkhanhama river by canoe to reach the village’s small harbor. Naatthembo can only be reached by car by taking the main road to Nampula and turning east just before reaching Namaponda. What follows is a mud road notoriously hard on any car. Shangaji speakers used to be found in the nearby village of Nthamala as well but when I went there on the 3th of February 2005, Makhuwa (Enlai) appeared to have taken over completely, which was confirmed by the people I spoke to and by my main language consultant Jorge Nlapa whose sister lived in Nthamala at the time. The only other village in the immediate area where Shangaji is spoken is Nakonya on the east side of the Sangage peninsula. People fled there from the mainland during the civil war in the seventies and eighties and although the inhabitants themselves still consider it a temporary settlement of huts (mapáantta) instead of houses (manyúumpa) at the feet of the white dunes (micíili) of the Sangage peninsula, they are likely to stay as fishing in Nakonya is very good. Some 60 km north of Naatthembo lies the town of Mogincual which houses a small community of Shangaji speakers in an area referred to as Likóokha. Shangaji speakers are believed to have come from the north of Mozambique, as far as Pemba, some stayed in Mogincual whereas others went further south eventually staying in Naatthembo. Shangaji speakers in Mogincual believe their variant is more pure and less influenced by Makhuwa than the variant spoken in Naatthembo. Speakers from the latter area, however, believe the reverse is true. I was able to note some phonological, morphological and lexical differences between the variants (see also Language Information below) on a three day visit of the area. In all Shangaji speaking area’s people provide in daily subsistence by farming and fishing. Fishing is done by line (oloówa) or by net (ociíya). Fishermen sail out on the tidal river or the ocean, they throw out the net and pull it back in from the shore. Women and children collect fish without a boat in shallow water (oraántta).

Language information

Shangaji (nte), eshangáaji (~eshángáaci) to the people, is a Mozambican Bantu language spoken in a few villages north of Angoche. The village called Naatthembo, which has approximately 4000 inhabitants, is its main centre. An alternative name for the language, enáattheembo, is derived from this village name. Some 500 more Shangaji speakers live in Nakonya facing the Indian Ocean on the Sangage peninsula which lies north of Angoche. They fled there during the civil war and although the inhabitants themselves still consider it a temporary settlement of huts instead of houses at the feet of the white dunes of the peninsula, they are likely to stay as fishing in Nakonya is very good. Another small community of approximately 700 Shangaji speakers is found some 60 km north of Naatthembo in Mogincual. The Shangaji variant spoken in Mogincual is referred to as eńcíinkwaáre. There are some minor phonological, morphological and lexical differences between these two Shangaji varieties, as the data below illustrate, but they are perfectly mutually intelligible.

The number of speakers is in fast decline because of the lack of intergenerational language transmission. When speaking to their children most parents resort to Makhuwa (Enlai). In the village of Nthamala, more or less 10 km northwest of Naatthembo, this language shift is total as the villagers no longer speak Shangaji. Next to being fluent in Makhuwa (Enlai) most Shangaji speakers also master Ekoti, the main language of the nearest town Angoche. Only few speakers are fluent in Portuguese, among which are my main language consultants Jorge Nlapa and Amina Sharaama.

Shangaji is the outcome of a past contact situation between a form of Makhuwa (vmw) and a form of Swahili (swh). Like three other Mozambican coastal languages (Ekoti, Mwani and Makwe) it differs from the Bantu languages spoken in the interior in showing clear Swahili affinities. Around 800 AD Swahili was spoken along the East African coast from Mogadishu in the north to Chibwene in the south. With the arrival of the Portuguese around 1500AD, the Mozambican Swahili communities became increasingly oriented towards the languages and cultures of the interior. Nevertheless, their grammars and lexica until today show traces of a past affiliation to the Swahili world.

Until the start of this project, Shangaji was largely undocumented. The Portuguese priest António Pires Prata wrote a short article on the language including some sociolinguistic and linguistic observations. Professor Thilo Schadeberg (Leiden University) refers to the language in two publications. He conducted some fieldwork on the language in 1995 and generously passed his fieldnotes on to me.

Special characteristics

The documentation of Shangaji is part of a larger documentation effort involving the so-called Swahili languages of Mozambique. The expansion of Swahili out of its homeland somewhere on the coast of northern Kenya probably started during the 7th century AD. The northernmost and southernmost boundaries are thought to be Mogadishu (Somalia) and Chibwene (close to Vilanculos in southern Mozambique) respectively. However, in southern Tanzania no old forms of Swahili have survived the 19th century spread of Kiunguja, Standard Swahili. The Swahili languages of Mozambique, including Ekoti, Shangaji, Mwani (wmw) and Makwe (ymk), prove that more southern varieties of the Swahili language group did exist. Their study and comparison will offer important insights into the history of Swahili along the East African coast. The documentation of Shangaji, the least known of the four, is pivotal within this larger study.

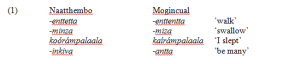

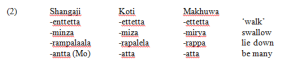

One phonological characteristic already observed by the Portuguese priest Antonio Pires Prata and confirmed by speakers of neighboring languages is the omnipresence of NC sequences in Shangaji, illustrated below in comparison to Ekoti and Makhuwa.

A detailed study (for which see Devos and Schadeberg 2014) of Shangaji’s “nasality” shows that Shangaji, like Swahili but unlike Makhuwa and Koti retained *NC̬. Interestingly, Shangaji also retained (or reintroduced?) *NC̬ in words for which a Makhuwa descent is more likely than a Swahili one. Second, Shangaji retained some *NC̥ where Swahili (and Makhuwa) lost them. A similar retention is found in Comorian. Further research is needed on a possible connection between Shangaji (and other Mozambican Swahili languages) and Comorian.

Collection contents

The collection contains a wordlist draft (with over 3000 entries), a grammar draft with chapters on phonology, nouns, minor word categories (adjectives, numerals, genitives, possessives, kinship terms, demonstratives, interrogatives, personal pronouns and clitics), verb morphology, verb inflection and predication. Additionally, there are 44 audio files with accompanying fully glossed transcriptions and English translations. Most are narratives or accounts of daily activities like fishing, house building, cooking, etc. During the second fieldwork trip, after having given birth myself, I also collected accounts of female matters like menstruation, marriage and pregnancy. Next, there are a number of fully glossed transcriptions without accompanying audio files the bulk of which are free standing sentences transcribed during fieldwork sessions with my main consultant Jorge Nlapa. These sentences are not translation equivalents but responses of Jorge Nlapa to my questions mostly formulated in Shangaji. Some of these sentences were later on recorded mostly to check prosodic matters. There’s also a number of audio files which are transcribed in the scanned notebooks but which have not been glossed and translated yet. Most concern grammatical matters and there are sentences describing scenes from the Put project and Reciprocals project videos developed by The Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics at Nijmegen University. Scans of my fieldwork notes and pictures taken during the first fieldwork trip have been deposited as well. In the years following the project my Shangaji database proved to be an important resource for publications on various linguistic topics. They have been included as well.

Collection history

The resources on Shangaji were collected during two fieldwork trips, one from January 2005 to the beginning of June 2005 and the other from April 2007 to the end of May 2007. Unfortunately, I lost all my luggage at the very beginning of my first fieldwork trip including almost all equipment. As a result, I had to resort to audio recordings only. Back home I digitized all the analogue recordings. In became pregnant between the first and the second fieldwork trip and therefore decided to stay in Angoche for the second fieldwork trip to assure contact with my parents who took care of my then 10 months old son. This limited recording possibilities as I worked outside of the village with Jorge Nlapa who came to Angoche to work with me and Amina Sharaama, a native of Naatthembo, who lived in Angoche at the time. External factors have thus somewhat hampered the documentation proper. However, I also need to admit that at that time I was probably still very much in a “descriptive” state of mind, having just finished a (traditional) description of Makwe for my PhD. Most processed data (grammar, wordlist, fully glossed transcriptions with English translations) were produced shortly after the first and the second fieldwork trip. The big delay in depositing the resources as well the processed data are partly due to engagements in other projects and partly to due to my own dissatisfaction with the overtly descriptive nature of the project outcome.

Other information

Please note that all the processed resources represent work in progress. Both grammar and wordlist are in need of updates and glosses require streamlining. English translations navigate between free and literal renderings of the Shangaji data.

Acknowledgement and citation

I am very grateful to all the speakers of Shangaji who helped me understand and speak their language and introduced me to their culture by doing so. Special thanks go to Jorge Nlapa with whom I worked on a daily basis during both fieldwork periods and to Amina Sharaama who very enthusiastically replaced Jorge Nlapa at the beginning of the second fieldwork trip. I also wish to thank the Lyndon family (SiL) who warmly welcomed me to their home (and electricity) in Angoche, Francisco Ussene Mucanheia who drove me from Nampula to Angoche and introduced me to some Naatthembo speakers in Angoche, Bento Sitoe from the Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo, for helping me find my way in Maputo, Leiden University for hosting me and especially Thilo Schadeberg for putting me on the Mozambican coastal track and also my parents for taking care of my son during my absence. Last but not least, I wish to thank Mandana, Sophie and Gema from Elar for (finally) making this deposit happen.

Users of any part of the collection should acknowledge Maud Devos as the principal investigator, the data collector and the researcher. Users should also acknowledge the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme (ELDP) as the funder of the project. Individual speakers whose words are used should be acknowledged by respective name(s). Relevant information is available in the metadata.

To refer to any data from the collection, please cite as follows:

Devos, Maud. 2018. Shangaji, a Maka or Swahili language of Mozambique. Grammar, texts and wordlist. Endangered Languages Archive. Handle: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-000F-B643-3. Accessed on [insert date here].